5 pillars

As mentioned in the previous section, INDIGO wants to build the basis to systematically document, disseminate and analyse almost 13 km of uninterrupted graffiti along Vienna’s Donaukanal (Eng. Danube Canal) in the next decade.

In doing so, INDIGO wants to digitally preserve this unique, complex, short-lived and socially relevant form of cultural heritage, as such leveraging its potential to disclose new socio-political-cultural research questions and graffiti-specific insights.

To accomplish those aims, INDIGO is structured around 5 research pillars of which the goals, challenges and expected results are detailed below.

To provide clean and relevant data for the spatial database and online platform,

- three-dimensional (3D) surface geometry of the Donaukanal,

- photographs of the graffiti, and

- auxiliary data must be acquired.

The 3D surface is vital to remove the geometrical image deformations (see B); it is also the backbone of the online platform (see D) onto which the graffiti images are mapped. The challenge lies in the acquisition of accurate and complete 3D geometry of the canal’s banks.

Although INDIGO can use the detailed 3D point clouds collected through Vienna’s Wien gibt Raum initiative (Eysn, 2020), some extra laser scanning and image-based modelling might be needed to avoid data gaps. The real challenges, however, relate to the photographic image acquisition.

Photographs should be colour-accurate and obtained as soon as possible after the finalisation of the graffiti. INDIGO solves the last issue through (personal) contact with many graffitists and Donaukanal visits on a two- to three-day basis (for which three photographers are available). A bi-annual photography campaign of the whole 6.6 km will allow change detection algorithms to pick up graffiti that went unnoticed.

However, reliable change detection, smooth transitions between overlapping images, and graffiti pigment identification all need colour-accurate photographs. Even if hard to achieve outdoors (Verhoeven, 2016), we expect to do better than anyone has accomplished so far.

Finally, relevant auxiliary data must be collected: graffiti metadata (like creation date, artist, graffiti type) or the videos and pictures that artists record during spraying. The challenge here lies in getting all the necessary metadata for every piece of graffiti. Many creators prefer anonymity, which is why the online platform will feature anonymous login for metadata entry.

All three datasets must go through one or more processing steps before being inventoried in the spatial database. As a start, all datasets receive the necessary metadata (e.g. IPTC tags for the imagery). The photographs will go through a strict routine to create 16-bit colour-accurate TIFFs (Molada-Tebar et al., 2019). The challenge here is to create a robust and repeatable workflow that maximises throughput.

Afterwards, an orthorectification process removes the geometric distortion of the images (Kraus, 2007). To that end, the 3D point cloud is meshed into a continuous surface, after which the tricky task awaits of segmenting and labelling the mesh into logical units (e.g. distinct physical structures like a bridge pillar or an underground construction element).

INDIGO needs a bespoke tool that can load just the necessary mesh segments to create orthophotographs and mesh textures. Ideally, this tool can also process the photographs that reside in the SprayCity archive. The bespoke software should also support the change detection operation required by the bi-annual photographic campaign described in pillar A, making its development challenging.

Finally, finding and documenting new graffiti is useless if the resulting data are not searchable. Therefore, INDIGO expects this tool to support image segmentation and annotation (e.g. new graffiti, old graffiti, no graffiti zones) and – through a spatial database link – the attribution of metadata.

Collecting and processing data without a sound data management system is irresponsible. This pillar aims to create a conceptual data model and implement it in a spatial database to manage and query all (meta)data. The need for a specific ontology, robust database integration with the online platform (see D), support for spatio-temporal queries, and adherence to the CIDOC CRM ontology standard make this task considerably challenging. At the same time, data entry should be customisable and painless.

Due to the existing Vienna-based OpenAtlas software (OpenAtlas team, 2020) and targeted programming, INDIGO expects its database and underlying data model to be an example for the Digital Humanities at large.

To tackle long-term digital preservation challenges, INDIGO will store all data in the certified ARCHE repository (Trognitz and Ďurčo, 2018).

An open access online platform ensures interactive visualisation and exploration of the data. Textured 3D views allow visitors to look at present-day graffiti in their geographically-correct urban setting or scroll through time and visually experience the works’ time-span.

A section to browse through detailed graffiti orthophotographs plus functions to download and extensively query (meta)data is also present. Although creating such a platform with slick user experience is a challenge (e.g. a pleasing layout, smooth data streaming, robust database integration), in a post-project future it could lead to an augmented reality app.

Even though articles and conference talks accomplish international outreach, they do not instigate the graffitists’ essential engagement. The latter is achieved via regular graffiti workshops and leaflet distribution by SprayCity. Combined with the QR-encoded stickers along the Donaukanal, these initiatives create the necessary local awareness to extend the foundations laid by INDIGO into the next decade (e.g. via citizen science).

Moreover, INDIGO plans two international symposia. The first one will take place six months into the project and tackle the technical aspects of recording, storing, and disseminating graffiti. Gathering experts so early on helps to avoid pitfalls further down the road.

A second symposium on graffiti’s socio-political and cultural impact is planned for the end of the project. This gathering marks the online platform’s launch and showcases how its stored graffiti (meta)data enables societal and cultural insights.

In this way, specialists in art history, philosophy, cultural studies, law, urbanism, psychology, and communication will see the potential of this massive open access archive, thereby ensuring this project’s transdisciplinary sustainability. Both symposia proceedings – planned to be published at their respective starts – might also become foundational publications on graffiti research.

Most of the scholarly literature on graffiti is exclusively descriptive, often devoid of essential metadata (e.g. Reinecke, 2012; Wacławek, 2011). This lead some scholars to blame graffiti research for its overall lack of academic rigour (de la Iglesia, 2015).

Given the exhaustive and spatially + temporally + spectrally impartial inventory of graffiti (meta)data, INDIGO’s open access archive will open new analytical pathways for graffiti research that support novel socio-political-cultural research questions. For instance, Vienna counts several legal spraying surfaces, collectively labelled as the Wienerwand.

Along the Donaukanal, there are approximately 300 m of Wienerwand. One may wonder if those who spray in legal graffiti zones have the same profile as those who do not, and if ‘artistic value’ and ‘legality’ are connected.

These walls could also offer insight into ‘dissing’, a phenomenon where graffiti – usually tags – are scrawled over a major (often solicited) graffito (McDonald, 2013).

Analyses like this also directly tie into existing graffiti definitions and classifications. Some scholars and graffiti artists voice that legally permitted graffiti do not deserve the label ‘graffiti’ (Tomàs et al., 2014). Even though such terminological distinctions do not guide INDIGO’s recording, the project must strive for terminological clarity to populate the database with unambiguous metadata.

The creation of a graffiti and street art thesaurus in the first project months will accomplish this. Being a finite set of terms (i.e. a controlled vocabulary) with hierarchical relations (Pomerantz, 2015), this thesaurus will make INDIGO’s graffiti/street art classification explicit and serve as a reference for the broader academic graffiti community.

methods and tools

INDIGO puts community engagement first. Without this local support and understanding, projects like this could develop asymmetric relationships between academia and the graffiti community. This community-based engagement is possible (and kick-started) through Stefan Wogrin from the graffiti archive SprayCity.

Stefan is familiar with the local graffiti community through his photographic activities and workshops for newbie and experienced graffitists. These activities allow INDIGO to establish project awareness amongst the existing and future generation of sprayers, resulting in the deliberate notification of new graffiti (e.g. via specific social media hashtags or QR code-linked forms). However, subversive writings will realistically only be noticed during the photo-surveys on a two- to three-day basis.

INDIGO complements these social participatory approaches with academic methods (like photography & photogrammetry) and tools (like databases & online platforms) common in heritage science. However, the mere usage of digital devices and techniques does not automatically imply their correct application, nor should it naturally lend credibility to a project.

Many of these approaches still have theoretical, methodological, and technical shortcomings. INDIGO wants to raise the bar in cultural heritage documentation and dissemination by improving many of these digital approaches.

Colour accurate photography necessitates a perfect mapping between raw camera values and colour values of a reference object. Since colour is a function of object reflectance and incoming radiation, both variables are measured with an X-Rite Ci60 spectrophotometer and a Sekonic C-7000 spectrometer, respectively. The pyColorimetry software (Molada-Tebar et al., 2020) leverages these data to colour correct the images. The latter are acquired with a Sony A7R IV (or similar) and Sigma Art prime lenses. Because all photographs should be equally detailed, a photographic pole and lenses with different focal lengths (e.g. 20 mm, 50 mm, and 85 mm) account for varying object distances.

A cost-effective GNSS/IMU (Global Navigation Satellite System/Inertial Measurement Unit) is connected to the camera to speed up image processing. This approach, previously co-developed by the PIs of this project (Wieser et al., 2014), automatically delineates the image’s outline (called footprint) on the photographed object. This information speeds up the orthorectification phase, as the 3D geometry and older photographs necessary for that corrective process can be selected automatically.

Meshing and segmenting the point clouds provided by the City of Vienna occurs in CGAL. These segments – which correspond to individual physical structures – are loaded into the photogrammetric toolbox to be developed by the TU Vienna. This bespoke Python or MATLAB tool takes care of image orthorectification, mesh texturing, change detection, and graffiti segmentation + annotation.

This software fetches data from the OpenAtlas spatial database. OpenAtlas is Digital Humanities-centred and supports the CIDOC CRM ontology. With this ontology, one can store graffiti data semantically, thereby enabling complex data querying and integration with heterogeneous data from other disciplines. With Alexander Watzinger – the core developer of OpenAtlas – onboard, INDIGO guarantees the necessary programming experience to integrate OpenAtlas with the TU Vienna tool and online visualisation platform.

Since INDIGO’s online platform will offer visualisation and querying of all (meta)data stored in OpenAtlas, users can find out what a certain graffito looks like, where it is/has been located and when it was visible (i.e. the time span). The accuracy of these queries depends on the spatial database structure (e.g. the metadata fields) and the values that populate the database fields.

Both aspects rely on clearly defined hierarchical terminology (i.e. a thesaurus) because it determines how graffiti gets annotated and which database structure accommodates this. Although INDIGO will use INGRID‘s practices as guidelines (INGRID, 2019), it aims to develop its own thesaurus of graffiti and street art terms. The technical creation of this thesaurus is facilitated by Vocabs, a tool developed by the ACDH-CH.

This platform is an open access website to interactively visualise and query all textual, 2D, and 3D data. The support and expertise of VRVIS facilitate smooth 3D data streaming. Whether visualisation will be taken care of by the VRVIS engine Aardvark, the dedicated 3D geospatial open platform Cesium or Epic Games’ Unreal gaming engine is still unclear. Visualisation and web technologies change quickly, so INDIGO takes an agile approach in this matter.

However, this platform becomes must avoid missing or erroneous graffiti metadata. Database entries will be created and curated by the INDIGO team, but artists can add or correct graffiti information through anonymous website login. With sufficient engagement of the local graffiti community, we envision that graffitists fill out the form that pops up when scanning one of the QR codes along the Donaukanal.

All the meta(data) acquired and derived in the framework of INDIGO will be stored at different processing states (i.e. raw and final data) within the CoreTrustSeal certified ARCHE repository. This approach ensures 24/7 data accessibility and digital longevity, which is still not taken seriously in the scientific community. Given its open data, open access and FAIR nature, INDIGO software tools will also be freely accessible.

work plan

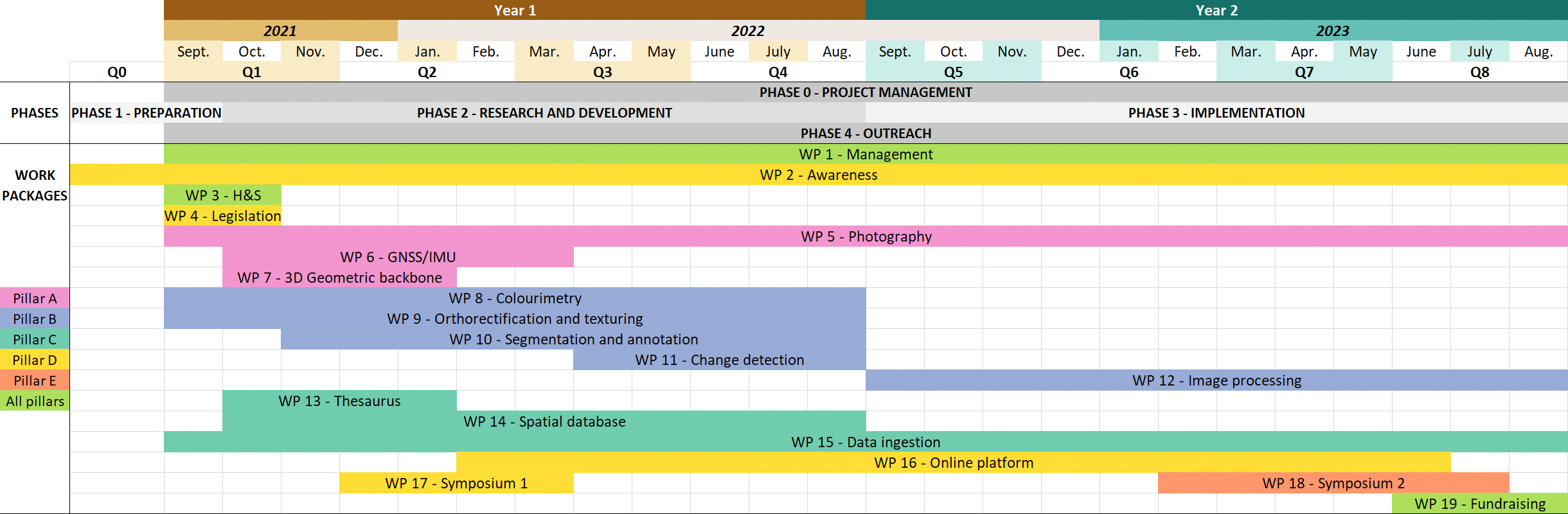

INDIGO is a two-year project which started the 1st of September 2021. INDIGO is thus spread over eight project quarters, with Q8 ending on the 31st of August 2023. Some activities like website and logo creation commended before the project start. They all fell within Q0 (see Gantt diagram).

Managing time and resources in INDIGO is supported by the project management tool Teamwork.

Workpackage no.

Short description

Timeframe

1

Management: daily project management, kick-off, and other meetings

Q1 to Q8

2

Awareness: creation of logo, social media, flyers, QR-stickers, leaflets, and basic website + SprayCity workshops

Q0 to Q8

3

Hard- and software acquisition: research and buy all necessary consumables to purchase

Q1

4

Legislation: sort out copyright and aspects of legal data sharing

Q1

5

Photography: daily and bi-annual graffiti recording

Q1 to Q8

6

GNSS/IMU: implementation + optimisation of camera coupling with GNSS/IMU devices

Q1 to Q3

7

3D geometric backbone: add-on photography and scanning to complement Stadt Wien’s point cloud + meshing + mesh segmentation

Q1 to Q2

8

Colourimetry: research and develop a workflow and tool for colour data acquisition + processing

Q1 to Q4

9

Orthorectification and texturing: research and develop a workflow and tool for photograph orthorectification and mesh texturing

Q1 to Q4

10

Segmentation and annotation: research and develop a workflow and tool for image segmentation and annotation

Q1 to Q4

11

Change detection: research and develop a workflow and tool for image change detection

Q3 to Q4

12

Image processing: colour correct, orthorectify, segment and annotate photographs with the tools and guidelines developed

Q5 to Q8

13

Thesaurus: research and develop a graffiti thesaurus and get community feedback

Q1 to Q2

14

Spatial database: research and develop the conceptual and logical data model with standardised metadata and get community feedback; implement the physical model in OpenAtlas.

Q1 to Q4

15

Data ingestion: link ARCHE with OpenAtlas and ingest all raw and processed data; also ingest images to SprayCity

Q1 to Q8

16

Online platform: research, wireframe, and develop a 2D platform with links to ARCHE and OpenAtlas. Research the 3D visualisation part and add it to the 2D platform

Q2 to Q8

17

Symposium 1: organising + contributions + proceedings

Q2 to Q3

18

Symposium 2: organising + contributions + proceedings; this WP also covers the database analyses (to be presented at this symposium)

Q6 to Q8

19

Fundraising: Stadt Wien + new project proposal

Q8